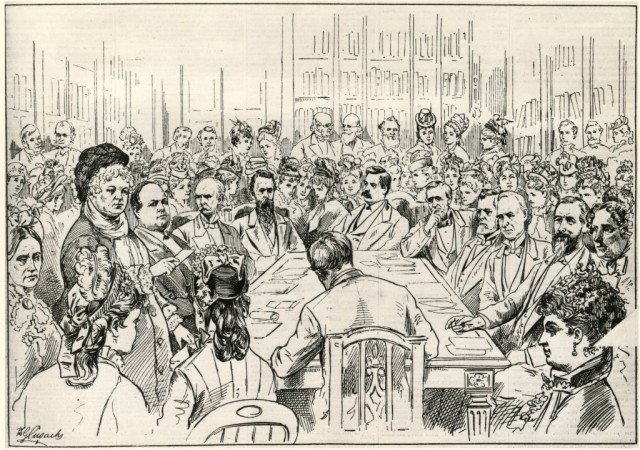

Several years ago I read this sympathetic and very public passage about a woman’s experience with drink. It appears in a speech by the Rev. Olympia Brown at a national meeting of woman suffragists in Washington in January 1885.

I stood to-day by the grave of Julia A. Roberts. . . . She had been divinely loving to humanity–careful and tender. She had provided lunches for poor men who could obtain no work. She had been a philanthropist and a patriot. She was a woman who had served her country well. But she had one serious failing–a failing common to our aristocracy of men–she was a victim to the wine cup. So sorrowful, lonely, and deserted–she died (Woman’s Tribune, March 1885).

I made myself a copy and stuck it in a folder, after realizing that research about a 19th-century woman named “Julia Roberts” would not go quickly.

I came back to it because it is a startling eulogy. In the annals of alcohol, respectable 19th-century women don’t get drunk, at least not enough to get their problem bruited about in polite company. The speaker said it: drink is a failing of men.

“The Drunkard’s Progress. From the First Glass to the Grave” Nathaniel Currier placed wife and child patiently waiting under the arch of the husband’s self-destruction in this chromolithograph from 1846. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Women were usually portrayed as the victims of men’s intoxication–left alone with children, challenged by drink’s drain on household finances, tested as to the depth of her love and loyalty by his misbehavior, and/or subjected to domestic violence at the hands of this drunk man. She was “The Drunkard’s Wife,” praised in poetry, song, and illustration for her willingness to forgive.

“The Drunkard’s Wife.” The fourth stanza of this 1850 song celebrated the all-forgiving wife: “And though it costs me many a pang to know the life he leads,/I’ll try to greet him with a smile though oft my poor heart bleeds.” (Music Copyright Deposits, Music Division, Library of Congress)

What was going on here that women were talking about Julia Roberts in death? Why was it okay to expose her as an alcoholic? And who was she? Newspapers and public records allow us to put a bit of flesh on Brown’s skeleton of Roberts, but the enduring story may be an unusual view that the death of Julia Roberts provides into sisterhood and equality as imagined and lived by a group of middle-class white women in the 1880s.

When Clara Colby, editor of the Woman’s Tribune, published Brown’s speech after the meeting, she added an editor’s note to let her out-of-town readers in on the story. Roberts “had been well known and highly respected in Washington,” she wrote of a woman she probably knew.

But on account of yielding to the temptation of the wine cup, society deserted her, and she died under very painful circumstances. The remains were cared for tenderly by the Woman’s Press Ass’n of Washington.

Perhaps that last explains who invited Olympia Brown, visiting from Wisconsin, to speak at the grave on January 21.

Brown and Colby both deployed conventions of the drunkard’s tale: Roberts died deserted, alone, and beyond the pale. The circumstances do seem to be quite dreadful and no doubt painful. According to the Evening Star, her “body was found yesterday lying in the floor of her room, 204 D Street, dead” (20 January 1885). According to her death certificate, she died the day before she was found. This single mother had sent her 14 year-old son away a week earlier to visit his aunt in Indiana.

The friends of Julia Roberts seem to be outing her as an alcoholic even while they rally round her, and they may exaggerate her situation. Press notices of her death were respectful and said nothing about drink. Just six months before her death, the addition of Roberts, that “brilliant and popular writer,” to the editorial team of the weekly Washington Times was heralded in a rival paper (Evening Critic, 18 June 1884).

Moreover, women’s embrace of Roberts in death seems to belie her purported isolation. It took Emily Edson Briggs, distinguished journalist and president of the Woman’s Press Association, less than a day to find the undertaker and inform him that “the funeral should take place from a private home.” Hers, the Maples on Capitol Hill (Evening Star, 19 January 1885).

Most sources agree that Julia was born in Alabama about 1845. According to her obituary, she married Finley Johnson of Baltimore at an early age. Johnson is a hard person to track, though he left a trail as a poet and lyricist. Most famously, he wrote one of the pro-Union versions of “Maryland, My Maryland” in 1862:

We hear the bugle and the drum,

We’re chasing off the dirty scum,

Thank God the Union forces come,

Maryland, My Maryland!

The marriage did not last long, reportedly because Johnson died.

On 7 December 1867, Mrs. Julia A. Johnson married John William Roberts, an English immigrant and clerk in the General Land Office. John also did not live long. Her obituary says he died in 1869 but that’s an error; he was alive at the time of the federal census in 1870, living with his wife in a boarding house, and in 1871, his son, John William, was born. Julia appears as a widow in city directories in 1875.

Julia had moved to Washington and, during the Civil War–again relying on an obituary–served as a nurse at a military hospital; that was the patriotic service to which Olympia Brown alluded. The work also marked the start of her public life out and about in worlds of Washington where women were conspicuous. Possibly she went from nursing to clerking in a department of the federal government–one of the city’s largest employers of women.

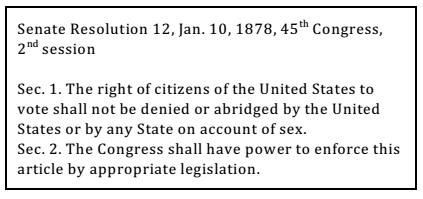

The peak of Julia’s fame in the city came in the late 1870s. During the long depression of that decade, she opened a Penny-Lunch House where the unemployed–sometimes more than 1,000 per day–could get healthy meals for a penny. To supplement what she raised through charitable events for the project, Congress appropriated money for her use in 1878 and 1879.

Along the way, at least by the mid-1870s, Julia joined the considerable number of women supporting themselves by writing for Washington’s newspapers. “Correspondent” was the word often given to her employment, likely meaning that she was not the employee of a particular paper but a writer who sold stories to papers. A sisterhood of the city’s journalists assumed the form of a club in 1881, later the Woman’s Press Association, of which Roberts was a member.

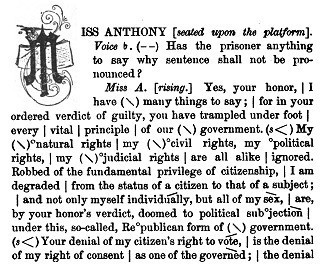

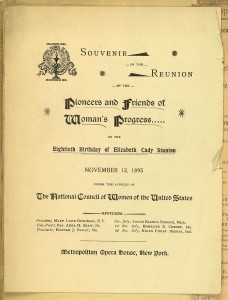

In the evening of 21 January 1885, back from Glenwood Cemetery to join the suffrage meeting, Olympia Brown wove a tale of Julia Roberts into her scheduled lecture, “All Are Created Equal.” Brown, a married woman raising a 10 year-old son, delivered a sharp, and occasionally funny, denunciation of the aristocracy of sex. “Ours is an aristocracy of bifurcated garments” that “maintains its superiority because it eats more.” Disproportionate power in the hands and rules of men affected nearly everything, she argued; this aristocracy “threatens to undermine all our institutions.” The life of Julia Roberts illustrated her points in several ways. Honors and economic rewards were not distributed equally: “A man who had done for his country what she had done would have been pensioned, and books would have been written about him.”

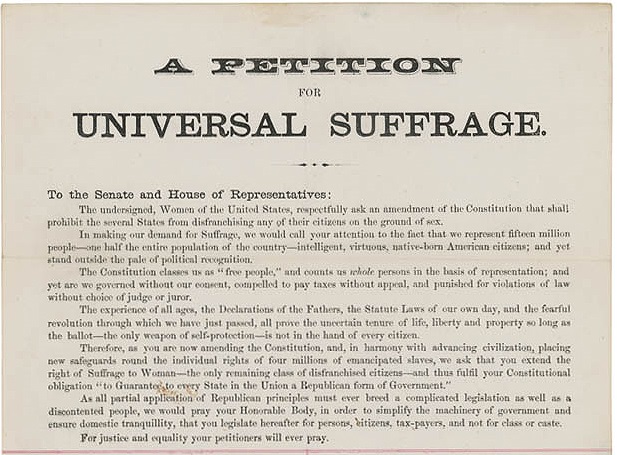

The word “pensioned” acts here as both a metaphor about recognition and a pointed political reference to inequality that her audience would recognize. An issue engaging women in national politics in the 1880s was the fight for federal pensions for nurses like Roberts. Pensions were paid to soldiers, their widows and children, but nothing was done for the women enlisted to nurse the wounded. In the last six months of Julia’s life, there were signs of change and promises to petition Congress for legislation. It would take four more years to win passage of the Army Nurses Pension Act, but just the new plan itself, announced in 1884, awakened and activated hundreds of nurses and their friends.

“The gentler sex – charity for the drunken brother, contempt for the unfortunate sister” by J. A. Wales, Puck 10 (21 September 1881) (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Brown gave equality another meaning too, one less easily measured. She blamed the illegitimate reign of an aristocracy of sex for the creation of “two standards of morality.” Sin is equal, she preached. How society reacts to sin is not equal. If a man of equal accomplishment “had been a smoker” or “had been drunk once or twice in his life,” the matter would have been forgotten. “Why, I ask in Heaven’s name, this difference?”

This was a persistent question in the 19th century, paired with pleas for good jobs, equal pay, and political rights. Jennie Collins, factory worker and labor agitator, had taken up the subject in her book, Nature’s Aristocracy (1871); women who stepped or slipped out of line, she observed, were not allowed the second chances extended to men. Taking a cue from a popular hymn to cap her argument, Collins quoted the line, “There is a light in the window for thee, brother,” and observed, “but no one ever heard of one there for his sister” (p. 57). Olympia Brown, like Jennie Collins, knew that this inequality of reputation and forgiveness had real life consequences for women in work, society, and family.

In the life of Julia Roberts, Brown saw an accomplished woman, brought down by burdens known and unknown, who deserved forgiveness and help.

It is just as wicked for a man to get drunk as for Mrs. Roberts. If it is deserving of eulogy for a man to serve his country and do nobly for humanity, then it is as noble in a woman. Sin is the same thing in a man as in a woman. If it is not agreeable to you that a woman should sin, let it be odious for a man to do the same. O! it is shameful that we should have different standards for God’s creatures.

Unlike the male cartoonist who ridiculed women for acting to redeem troubled men while turning their backs on troubled women, Brown spotlighted equality in action. She performed that equality in her own role at Roberts’s burial as well as in her telling of Roberts’s story at a large gathering of suffragists. Perhaps Brown also suspected that among the women in the room were some who had no tolerance for the weaknesses of their sisters; perhaps she preached to discover converts. The friends and acquaintances of Roberts had proclaimed, our place is not threatened by acknowledging this sister. We can set the terms of moral behavior.

§§§§

The research for this post could only be done because libraries have digitized newspapers. I could follow all sorts of public actions by Julia Roberts.

For research on the revival of the campaign for army nurses’ pensions, I am indebted to the thesis of an undergraduate at the College of William and Mary. Metheny, Hannah, “‘For A Woman’: The Fight for Pensions for Civil War Army Nurses” (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. http://publish.wm.edu/honorstheses/573